28 Weeks Later: When Perfect Security Meets Human Nature (Spoiler: Humans Win)

Six months after the first outbreak, authorities built the perfect secure zone. Then people started making exceptions to the rules, and everything fell apart again.

9/19/20257 min read

After watching 28 Days Later and counting all those security failures, I was curious to see how the sequel handled things. Six months after three activists with wire cutters nearly ended humanity, surely the authorities learned their lesson?

Well, yes and no. But first, 28 Weeks Later opens with a scene that perfectly shows what survival actually looks like when security protocols work.

When Security Protocols Actually Work

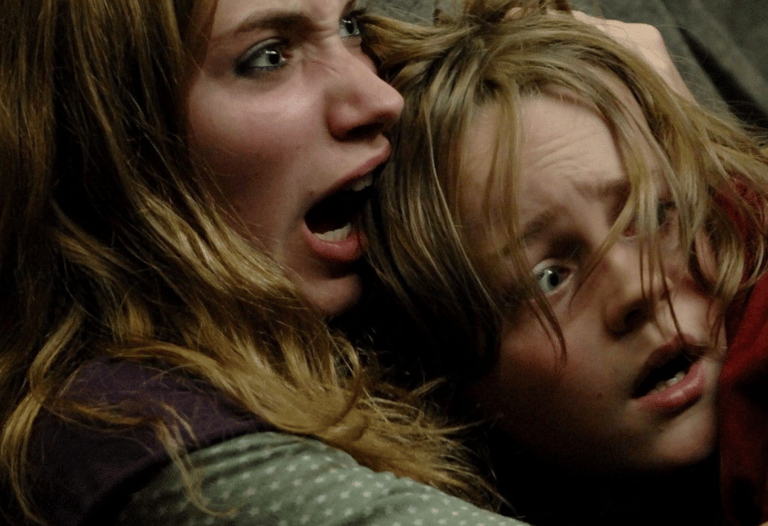

A group of survivors has found temporary safety in a remote house during the initial outbreak. They're following basic security measures: windows covered to block light, door secured, staying quiet to avoid detection. Then human nature takes over.

A young boy arrives, banging on the door until someone opens it - the first breach of their security perimeter. Karen, missing her partner and driven by curiosity, silently removes cloth from a window to peek outside. That small action creates the entry point for infected attackers.

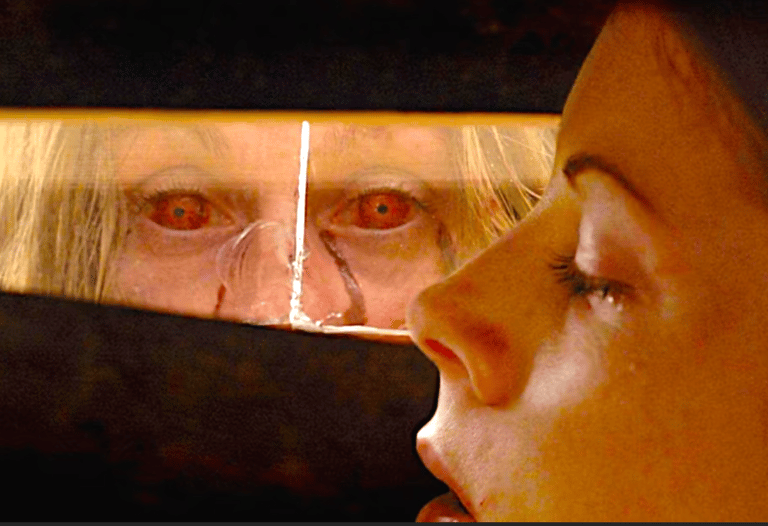

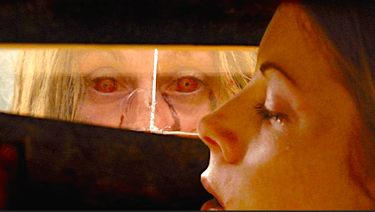

The infected break in. Karen gets bitten and turns. Chaos erupts. In the scramble to escape, Alice refuses to abandon the boy hiding upstairs, putting herself and Don at impossible risk.

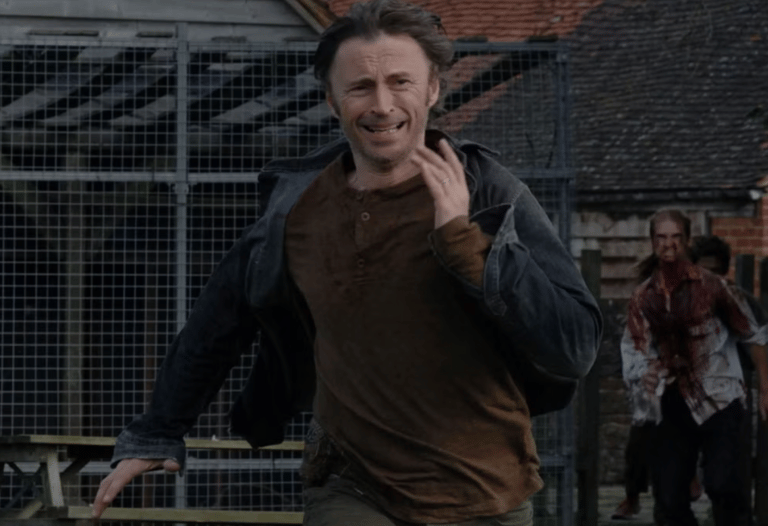

Don looks at his wife Alice begging him to save them both, makes the brutal calculation that attempting a rescue will guarantee everyone's death, and escapes through the window alone. He survives. Alice and the boy don't.

From a pure risk assessment standpoint, Don made the correct decision. He assessed the situation, realized that saving everyone was impossible, and chose to save who could realistically be saved. It was textbook triage thinking - harsh, but logically sound.

Six months later, this same man would make the exact opposite choice.

The Dream Security Setup (On Paper)

The film opens with District One, which looks like every security professional's fantasy. After the rage virus destroyed civilisation, the remaining authorities rebuilt from scratch with every possible lesson incorporated.

Multiple security perimeters? Check. Controlled access points? Check. Comprehensive monitoring? Check. Strict protocols for everyone inside? Double check.

It's textbook defense in depth - multiple security layers designed so that if one fails, others maintain protection. They built security into the system from the ground up rather than tacking it on afterward. On paper, it should have been bulletproof.

But then I watched people actually try to live within this perfect security system, and everything started making sense about why security implementations fail in the real world.

When Your Access Badge Becomes a Weapon

Don represents something I see constantly in security assessments - the dangerous combination of legitimate high-level access and catastrophically poor judgment. As a district administrator, he had access to areas most residents couldn't reach. This should have made him more security-aware, not less.

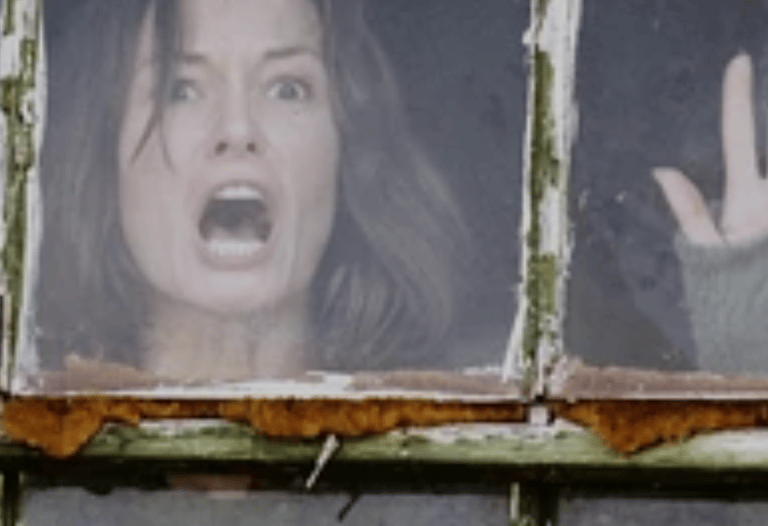

Instead, his emotional state made him exactly the wrong person to have an all-access pass. He was dealing with grief, survivor's guilt, lying to his children, then the shock of discovering his wife Alice was alive and being held for medical observation.

Here's what bothered me: why did Don have access to medical quarantine areas at all? What administrative function required him to visit high-risk medical facilities? This violated a basic security principle - people should only have access to what they actually need for their specific job.

Here's what bothered me most: When Don visits Alice in her quarantine room, he's in an area he should never have been authorised to enter. Alone with someone who might be a carrier, no monitoring, no safety protocols, no backup support. Neither of them knew Alice was infected - I assume she genuinely forgave him and he thought they were safe. The moment he kisses her, his legitimate access becomes the vector for the second outbreak.

The cruel irony? This is the same man who survived the opening scene by making the brutal rational choice to abandon people. But when it came to his wife, his emotions completely overrode those survival instincts.

This perfectly illustrates why access controls matter so much. It's not about not trusting people - it's recognising that anyone can make poor decisions under emotional stress, and those decisions shouldn't be able to compromise entire systems.

The Kids Who Broke Everything

Don's children, Tammy and Andy, weren't supposed to be in the quarantine compound at all. Children were specifically excluded from the security protocols. Yet there they were - someone made an unauthorised exception to established rules.

Within 24 hours of arriving, they'd identified surveillance blind spots, learned security guard rotation patterns, and successfully escaped the compound. They weren't criminal masterminds - they were just kids who wanted to retrieve personal belongings from their old home.

When the military found them outside the secure zone, they followed standard protocol: escort unauthorised personnel back to safety rather than leaving them outside the perimeter. This seems like good security procedure for normal violations.

But this is where I realised how security protocols designed for one type of threat can actually increase vulnerability to different types of threats. The escort protocol made sense for normal security breaches - it became catastrophic when applied to a potential contamination situation.

The Sniper's Impossible Choice

One of the most telling moments comes when a military sniper has clear shots at infected individuals but hesitates because they're children. His training says eliminate the threat immediately. His human judgment says wait, look for alternatives, hope for a different solution.

He chooses humanity over protocol. The delay allows the infection to spread further into the secure zone, ultimately collapsing containment entirely.

This isn't criticism of the sniper - it's illustration of why security systems can't rely entirely on human decision-making during crises. When emotions run high, when stakes are personal, when threats look like things that should be protected rather than eliminated, humans often choose compassion over security.

Modern cybersecurity addresses this through automation and clear escalation procedures. Critical security decisions are often automated specifically because human judgment, while valuable, can be compromised by emotional factors during security incidents.

Why Perfect Security Still Failed

What fascinated me about comparing both films was seeing different types of security failure:

28 Days Later: Solid security measures simply didn't exist. No proper access controls, no monitoring, no protocols, no backup systems. The activists succeeded because there was essentially nothing stopping them.

28 Weeks Later: Security measures existed but were undermined by human factors. The infrastructure was there - perimeter controls, access systems, quarantine facilities - but human psychology found ways around every measure. The tragic part is that Alice didn't even know she was infected, and Don thought he was safe with his wife.

Both films end in catastrophic failure, but for completely opposite reasons. The first outbreak happened because security was inadequate. The second outbreak happened because security was present but ignored, bypassed, or applied incorrectly.

This reflects a real challenge I see constantly: solving technical vulnerabilities is often easier than solving human ones. You can build better firewalls, but you can't reprogram human psychology. You can create stronger access controls, but people will still make emotional decisions that override logical protocols.

The Uncomfortable Balance

28 Weeks Later raises questions every organisation faces: How restrictive should security measures be? How much freedom are people willing to give up for protection? What happens when security protocols conflict with human needs and emotions?

The film suggests that purely restrictive security measures - no matter how well-designed - will eventually be undermined by human nature. People find ways around inconvenient restrictions. Authorised users make exceptions for personal reasons. Emotional factors override logical protocols.

This doesn't mean security is hopeless. It means effective security must work with human psychology rather than against it. The most successful security programs make secure behaviour the easiest option, provide clear explanations for why restrictions exist, and offer legitimate channels for exceptions when human needs conflict with security requirements.

Think about the last time you were frustrated by a security measure that seemed unnecessarily restrictive - complex password requirements, website blocks, or procedures that slowed down your work. Did you find a workaround? And looking back, do you think you understood why that security measure existed in the first place?

The thing that struck me most about 28 Weeks Later wasn't the zombie apocalypse - it was how every security failure came from people making reasonable human decisions that happened to be horribly wrong. Makes you wonder: when designing security, should we be trying to change human nature, or working with it?

Simple Terms Explained

Defense in Depth: Multiple layers of security measures, so if one fails, others still protect the system. District One had perimeter fences, access controls, and internal monitoring - not just one protection method.

Principle of Least Privilege: People should only have access to what they actually need for their specific job. Don's all-access keycard violated this principle.

Security by Design: Building protection into systems from the beginning rather than adding it later. District One was designed with security as the primary consideration.

Protocol Bypass: When users find ways around security measures they find inconvenient. The children leaving the secure zone despite knowing it was forbidden.

Human Factors: The psychological and behavioral elements that affect security. Why people make decisions that compromise security even when they understand the risks.

Containment Breach: When a security threat escapes the boundaries designed to control it. The infection spreading from the secure zone into the broader area.

Access Control: Systems that determine who can enter or use something, ideally limited to what's necessary for each person's role.